By Debra and Joel, on 1 September 2021 The following post was co-written by Debra and Joel, and published in 2018. Debra had intended to repost a previous article this month due to her travel schedule, but as it turned out, she returned to Michigan from a wonderful visit with Stacey and her family with COVID. Thus the choice of this subject!

Debra and John left Tennessee early Wednesday morning, August 25. They got news from Stacey that she had a headache and was going to get tested. She tested positive for COVID using the Abbott BinexNow at-home antigen test. Debra had onset of symptoms within about 24 hours, and John about 24 hours after that. Granddaughter, Courtney, also positive, and now great-grandson, Jackson, just 8 months old.

We were sure about a lot.

My friend’s mother died from COVID after her son, who was dealing with a wicked “sinus infection” visited his mother.

Perhaps this is a reminder of the importance of learning to stay willing to be awake and aware and ask, “Am I sure enough to be unsure?”

P.S. If you aren’t yet vaccinated, are you sure that is wise? If you are fully vaccinated, are you sure that you don’t still need to mask, limit travel, or otherwise avoid breakthrough infections? If you have had Covid, are you sure it is not your heart’s gift to donate plasma when you are able to do that?

Look around you at those who say no to war, who say that force is not the only way, and see that many of those spokespersons are using force to try to make their point; not force of violence but a force of confrontation that cannot compassionately hear others. Here is where you have special power, the power to speak to those whose view is close to yours but have not yet learned to overcome their fear-based attachment to opinions.

~ Aaron

“Are you sure enough to be unsure,” is a question asked in NLP to force a collapse of logical levels:

- Are you sure?

- Are you absolutely sure?

- Are you sure enough to be unsure?

When you are absolutely sure, you typically don’t question your certainty. If you are certain, for example, that today is Tuesday, when you are asked “Are you sure enough to be unsure,” the question opens the possibility of doubt, and you will probably check your calendar if only to prove to the other person that today really is Tuesday.

There are very few absolutes. What we typically consider absolutes are not necessarily absolute. Water usually freezes at 32 F and boils at 212 F most of the time, but a change in elevation changes that—as those living in high-altitude cities learned a long time ago. All things considered, the universe is fairly consistent in what is “true.” Most arguments, however, are based on differences in belief rather than on the physical aspects of the universe that can be measured in accepted ways. While scientists sometimes get into heated exchanges about the correctness of one theory over another, they typically use measurable details from the external environment as proof: they usually measure and weigh rather than yell and scream. They are more attached to process than they are to outcome.

Most of us, however, accept our beliefs as valid regardless of the external evidence. This seems especially true when it comes to religion and politics. When you are sure enough to be unsure, you check the external evidence to confirm or counter your belief. Most people, however, never question their attachment to a belief. In fact, they don’t even think of their belief as a belief. They think of it as an absolute truth.

Dr. Bruce Lipton, author of The Biology of Belief, describes the human experience of the “Programmable Mind” as thoughts, beliefs, and actions being truly conscious only 5% of the day. Babies are not born with beliefs. We are programmed by our culture, including our societal values and religious beliefs. Essentially 95% of the time humans’ hopes, fears, desires, and wishes come from the default program that resides in our subconscious minds. Under stress or duress we are essentially controlled by this programming.

So how can we shed our negative programming and create more from our wishes and desires when we live in a high-stress culture? First, we have to notice.

In Buddhism the practice is to observe our own attachment. “Attachment” in this sense of the word refers to something desired, a “must have” element that robs us of objectivity. It is, however, much easier to see when someone else has lost objectivity than to recognize “attachment” in ourselves. Related terms include frozen evaluation, an assessment that does not change over time, having a “closed mind,” and being unwilling to accept new evidence.

One of the most interesting dynamics is the way two people can consider the other attached without the awareness of their own fixed positions. And it is not just two people. The same dynamic influences not only political parties and national affiliations, but all other loyalties (states, corporations, unions, and families).

When we bring mindfulness to our own lives, we begin to consciously create the future we desire by our thoughts, words, and actions. Simple language patterns are very influential. Observe the different nuances between saying “As individuals are able to challenge their own most closely held beliefs, societies will be more mindful as well,” and using if or when to begin the sentence. When we speak from the heart and in the language of the soul—a language of trust, faith, and higher value; of inner growth, love, and listening—we open the door to possibilities. We become sure enough to be unsure, and that opens the door to increasing possibilities.

By Joel Bowman, on 1 August 2021 The saying is that the world ends, not with a bang but a whimper. I understand the sentiment. Ending with a “bang” is more appropriate for the young. I had plenty of opportunities to end with a bang, including automobile accidents and a tour of duty in Vietnam during the U.S. war there. So far, at least, I have avoided “going out” with a bang. In general, I think of that as a good thing, although I am not especially savoring the idea of going “out” with a whimper.

Surely there must be a third way, neither a “bang” nor a “whimper.” The idea that appeals to me the most is “curiosity.” I am, in fact, very curious about what’s next. People have, of course, wondered about what’s next for a long time. That’s where the concepts of “Heaven” and “Hell” came from: “Pie in the sky when you die” or fire and brimstone to punish the wicked.

While humans have been “supposing” about life after death for as long as humans have been been on the planet (and I’m not ruling out the possibility that other living beings don’t also engage in “supposing”), there’s no way to “test” the various theories people have had about what comes “next.” The only way to know what comes “next” is to die, and, while people have hypothesized about life after death as long as people have lived, we have no evidence that anyone has actually died and “lived to tell about it.”

Of course, people have claimed to have experienced an “afterlife,” either “Heaven or Hell,” and then attempted to profit from their versions of the afterlife. They do so, however, on the basis of scant evidence. I went to a “Christian” church once a week for most of my early life, and I am well-acquainted with traditional religious beliefs. Humans hate to think that life–and consciousness—will end.

The only way to conquer death is, of course, to die. And while many have claimed to have returned from the dead, there is no actual evidence that anyone has done so. We would, I think, do well to focus on making our daily lives as good as they possibly can be, and that would include helping others have good lives as well.

I would be curious to know what others think.

By Debra Basham, on 1 August 2021 …our culture,

and also a lot of psychotherapies,

demonized various parts of us,

and think they are what they seem to be—

which never turns out to be the truth.

~Richard “Dick” Schwartz

No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model

One of the presuppositions of NLP (Neurolinguistic Programming) is that behind every behavior is a positive intention, and that people are always doing the best they can at that moment, given the resources available to them.

This fits well with the Internal Family Systems Model (IFS) of individual psychotherapy Schwartz developed in the 1980s. Think of “parts” as relatively discrete subpersonalities, each with a unique viewpoint and qualities.

…before they got hurt, they were these what are called playful inner children; you’d love to be around them, because they have so much creativity and delight in the world, and want to be close to people, and a lot of innocence and playfulness. But after they get hurt, or terrified, or shamed, because they’re often the most sensitive parts of us—so traumas, they’re the ones who take in those burdens the most of fear, or worthlessness, or emotional pain, or sense of abandonment, or so on—once they get burdened by those feelings, we no longer want to be around them anymore because they have the power now to overwhelm us with that and make it so we can’t function or think a lot of the time. ~ Dick Schwartz

Having just completed a three-year intensive study called Dharma Path with Barbara Brodsky, Aaron, and John Orr, this is all very familiar: “Nothing that is of beauty and goodness is ever lost. The knowing of this is the gift of the dharma path, and the blessing to meet the teachers and the tools and the practices that can allow you to follow that path… And yes, I fully trust this path and that it will bring you home.”

Riding bike with a friend early one morning, I shared the story of Milarepa, the great Tibetan saint. The story is told masterfully as Into the Demon’s Mouth by Aura Glaser, published in Tricycle, the Buddhist Review. Milarepa’s story demonstrates that we can learn to face our fears with clarity and kindness.

None can deny the damage that is done by not doing so….

Everybody around us tells us, “Just move on. Don’t look back.” So, we lock them away, not knowing that we’re locking away our juice, and thinking we’re just moving on from the memories of the trauma or the emotions of the trauma. When you get a lot of exiles, you feel a lot more delicate, the world feels a lot more dangerous, and other parts are forced into these protector roles out of their naturally valuable states, and they become the critics, or they become the bingeing parts. ~ Dick Schwartz

The bingeing parts are within us all. Humans binge watch Netflix. Humans binge on exercise. We binge on wholesome and unwholesome thoughts, beliefs, and actions. We binge on political debates, prayer, health food, junk food. We binge on hate and even on romantic love.

When we don’t acknowledge all of who we are, those unacknowledged parts will land in what Jung called the “shadow” that we then project onto others, writes Glaser in Into the Demon’s Mouth.

But, perhaps, humans really can get curious enough to discover what our “parts” have been trying to protect us from, and we can get free by setting those parts (Schwartz calls these parts exiles) free.

Then I would have you, in your mind’s eye, enter that scene and be with her in that terrible time, and the way she needed somebody, which is a process we call a retrieval. We would do that until she was ready to leave with you and come either to the present with you or to fantasy place that was safe. Once she was there, I would have you ask if now that she trusts she never has to go back there again, if she’s willing to unload the feelings and beliefs she got from those times. Most of these exiles are at that point willing to give all that up because they know now they’re safe. ~ Dick Schwartz

Behind the behavior of unloading the feelings and beliefs that we got from painful or traumatic times in the past is the positive intent of having all the parts of us know now they’re safe and YOU can go on and enjoy the rest of your life.

By Joel Bowman, on 1 July 2021 The saying is, “All good things come to an end.” A fuller truth is that all things come to an end. Somewhere else on these pages I quoted the old saying that the light you see at the end of the tunnel is the headlight on a train heading in your direction. At this point, I am old enough to be aware of just how close to the end of the “tunnel” I am getting. I am, however, not complaining.

All things considered, I have had a very good life. I had a number of friends and acquaintances who didn’t get out of Vietnam alive. I also had a number of friends who did not avoid or survive highway mishaps.

A very long time ago, I was complaining about the prospect of death to my father and “scolded” him by saying that he, too, would die. His reply was, “Yes, but I will have lived first.” The implication was that I need to spend less time worrying about the inevitability of death and get on with the process of living. That is still something I believe.

If you think of life as a metaphorical journey up one side of a mountain and down the other, youth is our time for climbing up the mountain before we start down the other side. At first, the downhill portion is easy, The farther down the hill you go, however, the more difficult, it becomes to stay on your feet and to select the best path.

I have been one of the lucky ones, not only for the journey up “the mountain,” but, so far at least, for the journey back down. Of course, I am just now reaching the point that the “downhill side” becomes increasingly treacherous. I no longer drive, for example. I am still physically capable of driving, but I don’t consider it safe—not for me or for others on the road—so I let younger friends and acquaintances do the driving for me.

I am increasingly aware that physical activities are more challenging than they used to be. It doesn’t seem that long ago that I was in the habit of running 5 to 10 miles a day—before walking from my home to the college campus where I was teaching. Whether we like it or not, however, the clock keeps on ticking, and the months on the calendar keep going by.

I have indeed been one of the lucky ones. I have managed to get through a relatively long life with very few physical problems. When I have quit activities (such as driving) it has been because I have chosen to quit. Yes, I know that I will die, but I continue to be determined to live all I can first. I encourage you to do the same.

By Debra Basham, on 1 July 2021 So many times over the years I have found myself sharing how the ambiguity of language is both a hindrance and a help. You may recall that Neurolinguistic Programming has been described as the study of the structure of subjective experience.

The key word here is SUBJECTIVE.

In the Karaniya Metta Sutta (The Buddha’s Words on Loving-Kindness) we are invited to be unburdened with duties. Barbara Brodsky opened the June 13, 2021 “Remembering Wholeness” event by recapping her previous night. She described the reality of being a deaf wife whose husband had a stroke that left him unable to speak (or move his right side). He is no longer capable of using sign language to speak to her.

Until covid shut down the facility Hal was living in, she could sleep through the night. Then she brought Hal home.

Systems being what they are, they lost Medicaid and Hal’s care became a totally “out-of-pocket” expense. Thus, Barbara finds herself on overnight duty every night, and while Hal sleeps through the night on most nights, he had not done so the previous night, and she had to teach.

Barbara quoted the Metta Sutta before she shared about her overnight experience and spoke these words:

Those of you who are mothers and fathers, do you remember how it was when our babies woke us at 3am? Over and over…. Walking the baby who was fretful, whatever.

Ahhhh.

So, finding the light, finding the love, down there in that place of burden.

I guess this is not meant to be a Dharma talk, I’m just trying to share with you. And it’s not always clear – I’m not always able to speak clearly about something I’ve just experienced.

But where is the light with the darkness of burden, or duty, or ‘I should’ and the finding of the heart that says: “I choose to. I do it out of love.”

ALL of this is filled with nominalizations!

Nominalizations are nouns that are created from adjectives (words that describe nouns) or verbs (action words). For example, “interference” is a nominalization of “interfere,” “decision” is a nominalization of “decide,” and “argument” is a nominalization of “argue.” “Love” is a nominalizion of “love,” and “light” is a nominalization of “light.” A nominalization is a noun (a naming word) for something cannot be put into a wheel barrow.

If you say HOUSE, a house is something that could be put into a wheel barrow, albeit a very big wheelbarrow.

As we speak words outside that mean something to us inside, we are using nominalizations.

“I like music that is calming.” Well, for some that is jazz!

“She is smart.” Hmmm, by what measure?

“This is easy/hard/fun/frustrating.”

One of my favorite subjective experiences is riding a bicycle. I found this paragraph describing how to let bicycling be for you one of life’s secrets to happiness:

Go hard when you need to work out frustrations. Go easy when the sunset is beautiful to behold. Take the road when you want to get there ASAP. Take the path when you’ve got time to take in some nature and rebalance. Happiness is there for you to take when you hop on your bike.

Words that describe an experience are very subjective. Case in point are some words from Daily Loving Reminders, by Betty Lue Lieber:

Stop telling stories that only teach tragedy and fear, humiliation and grief.

Stop digging up what is meant to be dead, done and buried.

Stop reminding yourself and others what was done long ago.

When we cling to the old stuff we become old stuff.

Life teaches us renewal.

Our skin sheds and renews itself.

Our bodies are ever-renewing structure.

Our minds, too, can be easily undone and redone.

It is our choice to clear out what no longer serves us.

It is our choice to clean up our own addictions and unhealthy habits.

It is our choice to let go of activities and people that no longer inspire us.

It is our choice to make amends and begin again with a new spirit and new life.

We can begin to notice how subjective EVERY experience is.

In fact, EXPERIENCE, even a shared experience, is always subjective.

By Joel Bowman, on 1 June 2021 I am old enough at this point to be fully aware that I am close enough to the end of the tunnel that I can see it. There was a time that the end of the tunnel was a vague light in the distance. At this point, it is close enough that I am beginning to see details. The old joke is that the light at the end of the tunnel is a train heading in your direction. That is, of course, a metaphorical joke.

Everyone’s life eventually comes to an end. While I think we are right to to postpone reaching the end of our particular tunnel as long as we can do so ethically, we need to be aware that everyone—no exceptions—everyone eventually reaches the end of the tunnel. A number of my friends from grammar and high school reached their end of the tunnel early. Quite a few of my friends from my time in the Army reached the end of the tunnel before they were discharged. Some lost their lives in combat, while others died while driving drunk.

I have been among the lucky. I have avoided early death. That doesn’t mean that I have avoided death. I am not yet counting hours or days, but I am increasingly aware that the character often called “The Grim Reaper” is “out there” waiting. My sense—my belief—is that both Heaven and Hell are metaphorical. So … what happens next? That, of course, is the main question. Most of our ancestors envisioned a “Heaven” where the “good” people went for their eternal reward, and a “Hell” where the “bad” people went for their eternal punishment.

We (people—all people at all times) make up stuff we think will happen in the “after life.” Even those people who think that there is “no ‘there’ there” are making it up. Some claim to have been visited by “dead” ancestors who described the “after-life” in great detail. No one can of course do better than the Buddha of Debra’s story.

Whatever you believe, the chances are good that it is at least partially true. It is also at least partially false. The only way to know for sure is to die. When I was a young child and concerned about death, I complained to my father, saying that he, too, would die. His response was, “Of course. But I will have lived first.” That is, after all, all we can do. Live to the best of our ability for as long as we can.

At some point, we can hope to meet Buddha and Jesus. And then we may get to do it all again….

By Debra Basham, on 1 June 2021 If we are aware in a compassionate, focused way, we plant seeds of compassionate focused awareness that lets things go and lets things be. Joyful feelings are free to arise without creating clinging, and painful states can arise without expressing themselves in harmful ways.

~ Ben Connelly, “Cleaning Out the Storehouse”

I’ve been reading a new release by Oprah Winfrey and Dr. Bruce Perry: What Happened to You?: Conversations on Trauma, Resilience, and Healing. This book looks at the neuroscience of brain development and trauma. And get this straight — although some people live through more agreed-to-be-traumatic experience than others, all human beings develop through this lens of the reptilian brain.

From What Happened to you?: “Your brain is doing exactly what you would expect it to do considering what you’ve lived through.”

This all fits in with SCS/NLP perfectly.

Imagine if every ‘acting out’ behavior was met with this kind of reassurance!

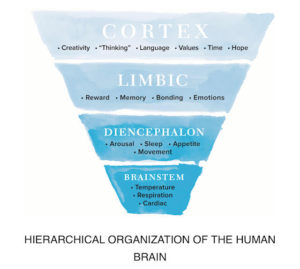

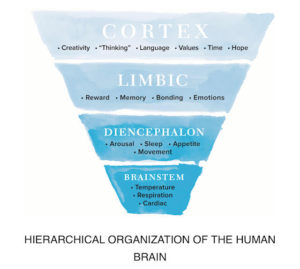

Even the diagram of the hierarchical organization of the human brain from What Happened to You? correlates to the information on the Drama Triangle (as developed by Stephen B. Karpman, M.D.), along with a Cognitive Triangle and Transrational Pyramid presented in Healing with Language (Bowman and Basham, 2008).

Recently I had a text-message exchange about a 2019 docudrama titled “Dark Waters,” based on a lawsuit against DuPont for dumping millions of pounds of cancer-causing chemicals into the Ohio river. (See: DuPont c8 Litigation)

I copied a summary sentence from fact-check in my reply to the person who suggested I watch “Dark Waters”: “Just because there really is something in the water doesn’t mean you can’t also be paranoid.”

You may not have previously considered how each of us developed through this Drama Triangle.The Drama Triangle is the impetus for all of our social programs, every one of our political opinions, and even our religious beliefs – regardless of what religion we have chosen to participate in.

Wondering now if you will join me as we imagine a world without this being the case….

Yes, every experience flows through our reptilian brain (brain stem), but our reactions do not have to come from there. Thankfully, we also have a cortex!

You can think of your frontal cortex as your working memory. This is where you have high-level cognitive function: thinking clearly, having a sense of how things are connected…. these spontaneously generate effective social-emotional evaluation of stimuli.

I have not read all of What Happened to You?, but I have already begun sharing information with others.

In Healing with Language, we learn to listen to the words and phrases others use. We also learn to pay attention to when a role has been activated within us.

Here is a partial list that helps you can pay notice the language of the Drama Triangle:

I can’t…, you won’t…, this always happens to me…, nothing ever goes my way….

You always…, you never…, you must…, if you know what is good for you, you will…

You can count on me…, let me help you…, let me do that for you….

Watch out for universal quantifiers and qualifiers, implying erroneously that something s-t-r-e-t-c-h-e-s across all times and contexts.

By contrast to roles, the Transrational Pyramid describes you as an awake and aware observer. Seeing that the real battles are all within, one begins to trust the process of life, and accepts and loves what is because it is part of the All That Is.

That doesn’t mean that we have given up involvement in beneficial causes and activities. We do so from a more peaceful and less judgmental perspective.

There is an often told story of the Buddha. He was walking down a road after his enlightenment when a man stopped him, being struck by the deep peace and joy that radiated from him. “Are you a God?” the man inquired.

“No,” the Buddha replied.

“Well, what are you?” the man asked.

“I am awake!” came the answer.

Perhaps that will become the most clear understanding of what happened to you….

* You can read the entire article by Ben Connelly, “Cleaning Out the Storehouse,” at Tricycle Magazine.

By Joel Bowman, on 1 May 2021 John Lennon of Beatles fame is reported to have said, “Life is what happens while you are making other plans.” In general, that seems to be true. We spend a lot more time planning what we will do than we spend doing it. And very few things go exactly as planned.

That automatically entails more planning. And, of course, once the new plan is viewed and evaluated, more planning becomes necessary. Two steps forward, one step back, is the way progress tends to be measured.

If you have seen any of the movies about life in previous centuries you know that human progress has never been easy. Our ancestors knew that better than we do. Sailing vessels needed the wind to move, so the only way they could move in a different direction from where the wind was blowing was by “tacking.” They would have to go first in one direction, and then change directions, moving in a “zig-zag” fashion.

As long as vessels were powered by the wind, tacking was the only way to go in a direction that the wind wasn’t blowing. We tend to forget how much “tacking” has been has been required to get humanity where we have wanted to go (even when we could agree on where we wanted to go).

When you change plans to better attain a goal, you are essentially “tacking.” In general, you have to focus on your desired objective while you “tack” in different directions even while keeping your ultimate objective in mind. If you don’t have a goal in mind, you end up going wherever the wind takes you.

Tacking requires staying focused on a goal even while you change directions from time to time. And sometimes, of course, changing directions leads to finding a completely new direction that will lead to even greater progress.

Is what you are currently doing leading you in the right direction and giving you what you want? If not, there’s nothing “tacky” about “tacking.” Change directions. That is, after all, the way our European ancestors found the “New World” that led to the creation of Canada and the United States.

In general, when you are “stuck,” do some “tacking” and change directions. See what new worlds you might be able to find. Two steps forward, and one step back is a perfectly good way to make progress, isn’t it….

By Debra Basham, on 1 May 2021 A friend shared a page from The Light of Discovery, by Toni Packer. Toni Packer was a teacher of “meditative inquiry”, and the founder of Springwater Center. Packer was a former student in the Sanbo Kyodan lineage of Zen Buddhism, and was previously in line to be the successor of Phillip Kapleau at the Rochester Zen Center. She was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1927. This is an excerpt from the chapter titled, Yearning for Completion:

From the thought-feeling of incompleteness arises wanting and fearing. Wanting completion and fearing the absence of it. Wanting fulfillment, meaning, and purpose. Wanting and fearing.

In observing carefully, one finds not a moment goes by without some wanting or fearing. Even if there is a moment of fulfillment, there comes the desire for more of it or the fear that this moment will end. One wants to keep it, wants to prolong it. All of it comes out of this feeling of incompleteness, which inevitably goes with the idea of “me” as a separate entity.

~ The Light of Discovery, by Toni Packer

NLP draws heavily on the use of metaphors. By telling a client a story that is both relevant and symbolic, we are essentially using a metaphor to bypass conscious resistance and thereby allow the client to make connections at a deeper level.

Essentially all language is metaphorical.

Metaphorical magic is the artful use of language.

And everything is part of the magic.

The specific story you choose.

The tone of voice with which you tell the story.

The timing of the delivery of each word or phrase.

We understand this very clearly as it relates to our telling someone else a story, but I am wondering if it is perhaps even more powerful when we notice the stories we are telling ourselves.

The following “past-life story” was told at a week-long meditation retreat, by Aaron, channeled by Barbara Brodsky:

I was a fisherman. I could go off for a day or a week, had ample water in my boat and basic supplies. I navigated by the stars. I always knew where I was, unless it was cloudy and rainy, and I also knew that eventually the clouds would pass, the stars would come out, and I would know where I was again. So, I didn’t worry much about non-existent compasses and other such tools.

I could always catch fish to eat. I was in no danger of starving anywhere. I carried a small bit of water, enough for several days. I would never be further than several days from land, where I could get fresh water. If it was clear, I would be able to find land easily, navigating by the stars. If it was not clear, it would probably be raining—again, plenty of water.

My life was quite relaxed. I would go out for a few days, bring home a cargo of fish, bring them back to my village, rest for a day or two at home, and go back out again. I loved my life. I had a wife and children, parents, siblings, friends. There was always joy, singing and dancing. Life was good.

Then I was caught in a severe storm and blown for 4 or 5 days, completely off course. My mast broke. My rudder ripped off the ship. Once the storm passed, I had just a paddle with which to propel myself.

I came to an island, was able to make shore on the island in what was the very broken remains of my boat. It was a small island; I walked all the way around it. There was one good sized hill in the middle. It was rocky along one shore, more sand and some coves on the other shore. A few small caves nestled in the rocks of the hill. There were a few small animals and a somewhat brackish pond. I suppose between rainstorms that’s where the animals came to drink. But there was enough rain, not really ever a dry season, so that small galleys and hollow would fill with water between rains.

I was heartbroken. I did not know how I would get home. I was able to read my location from the stars and saw how far off my course I had been blown. It would not have been a problem, if I’d had a proper vessel, but my boat was broken beyond much further use. I had nothing to use for a sail. So, I knew how to navigate my way home, but I did not have a boat to bring me home.

I was far enough off course that it was unlikely anyone would come looking for me there. Interestingly, while I loved fishing and I loved my family, I was grateful for the time that I had. All my life I had wanted to be more of a spiritual man, perhaps to be a shaman and connect with the various energies of the earth, of plants, of the animals. To have more quiet time, which time was mostly denied me as the father of a large family.

So here I was, on this truly idyllic island. Me, a fisherman—a very competent fisherman—and an abundance of fish. Adequate water, adequate shelter. Why would I wish for anything else? But I was heartbroken. I wanted my home; I wanted my family. I wanted my old life back.

Weeks passed and turned into months. I learned all the different plants of my new island, what were good for medicinal purposes, for example; which ones could be cooked and added to fish to create a tasty meal. Herbs that added flavor.

For the first year, I was very focused on “I want to go home.” But gradually, I relaxed and began to find real joy in my day-to-day existence.

I cleaned up the inside of the cave, added matting to the floor to make a comfortable place to lie down at night, a shelter. I created a good cooking area. I found coconut palms. After eating the inner fruit, had the shells; created a working set of eating utensils and food preparation utensils. I found spiny thorns of cactus and from fish and turned them into sewing needles. I found vines that I could use as thread to sew myself something to keep me warm and protected from the sun, and immense leaves thick enough to give some protection, .

My life settled down. There was no longer grasping. Sometimes yes, I missed my family, I felt sad. But there was no longer grasping, “I must go home! I must go home!” Increasingly I experienced gratitude for this gift of solitude I had been given. I spent many hours a day in meditation and reflection. I learned much better how to co-create with my environment and with love for that environment. There was gratitude for each living part of the environment, animate and inanimate.

The thought began to open, no longer, “I want to go home! I must go home!” but, “For now I am here, and I am grateful. I hold in my heart to see my family again. I know that one day I will see my family again. What can I bring back to my family when I eventually see them? What gifts will I have gathered here to bring to them?” And so, I gained deep knowledge of the plants, not too different from those of my home island. Deep knowledge of how to grow things; different cooking skills; a strong body; deep spiritual awareness.

One day some years later I saw that I had a very different approach to my life — enormous gratitude for all I was learning.

Take some time to notice what stories you are telling yourself. See if a new story, a kind tone of voice, a well-timed delivery of the meaning of the message might mean your different approach to life has resulted in a time in which you now have enormous gratitude for all you are learning….

Now, that, dear friends, is a magical metaphor!

By Joel Bowman, on 1 April 2021 The old saying is, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names can never hurt me.” It isn’t true, however. Sometimes names are the most hurtful of injuries, leading to shame and embarrassment that last much longer than any associated physical injury. Another very old saying is, “Actions speak louder than words.” While generally true, it isn’t an absolute. Sometimes I wonder why more of what we say and do isn’t directed at being kinder to one another, Notice how much of human history is dedicated to war and how little is actually dedicated to peace.

The old song is “Ain’t Goin’ to Study War No More,” but it is very hard to get away from the “study” of war. One of the ironies is that the “study” of peace actually ends up being the “study” of war. If people wanted to just “do” peace, they would/could just “do” peace. Instead, they have to look for ways not to “do” war. I may be the only regular reader of the Beyond Mastery Newsletter who has actually been to war. I am a Vietnam veteran. I spent three years in the U.S. Army during the war in Vietnam, and spent a year of that in Vietnam.

I was one of the lucky ones who was never close to actual combat. But I know what it was like to be in a combat zone, and to need to watch carefully where I walked to ensure that I didn’t step on an “IED” (Improvised Explosive Device) buried along one of the paths the U.S. soldiers used on the way to the “Mess Hall” or to the latrine.

The week before I arrived “in country,” one of the soldiers in my unit had stepped on an “IED” and lost a leg as a result. Soldiers in the company needed to be aware that they were in a combat zone and that “the enemy” was constantly looking for ways to kill or injure U.S. troops. I didn’t meet Debra until long after I had returned from Vietnam, so in some ways she doesn’t know who I was before I met her.

Does spending time in a combat zone change a person? I think so. One of the problems is, of course, finding those who have been in combat zones and NOT been in combat zones. My sense is that being in a combat zone changes the way people look at things. People who have never been in a combat zone simply see things differently from those who have been in a combat zone. My father saw combat in WWII, and his advice to me before I went to Vietnam was to find “an experienced sergeant” and stick with him when we were attacked.

My father and one of his friends had been having lunch while sitting on a log. They were strafed by a Japanese fighter and fell on opposite sides of the log. My father’s friend was killed. My father was unhurt.

I was one of the lucky ones. I spent almost a year in Vietnam during “the war,” and although I did not experience actual combat, I was constantly aware of where we were and what could happen next. I was definitely glad to leave Vietnam when my turn came. Some of those I called “friends” never made it back to the States. I well understand why people don’t want to “study war” any more.

|

|